Cause of kicks

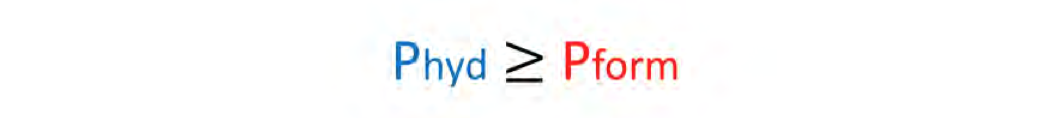

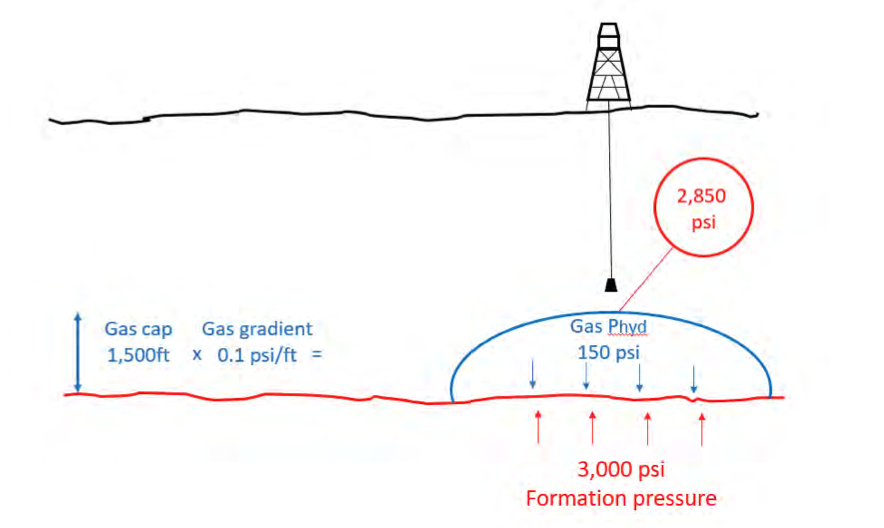

As we have already seen primary well control is when hydrostatic pressure is greater than or equal to formation pressure – the pressure pushing down is greater than or equal to the pressure trying to come in or pushing up. If we were to describe primary well control as a formula we would get:

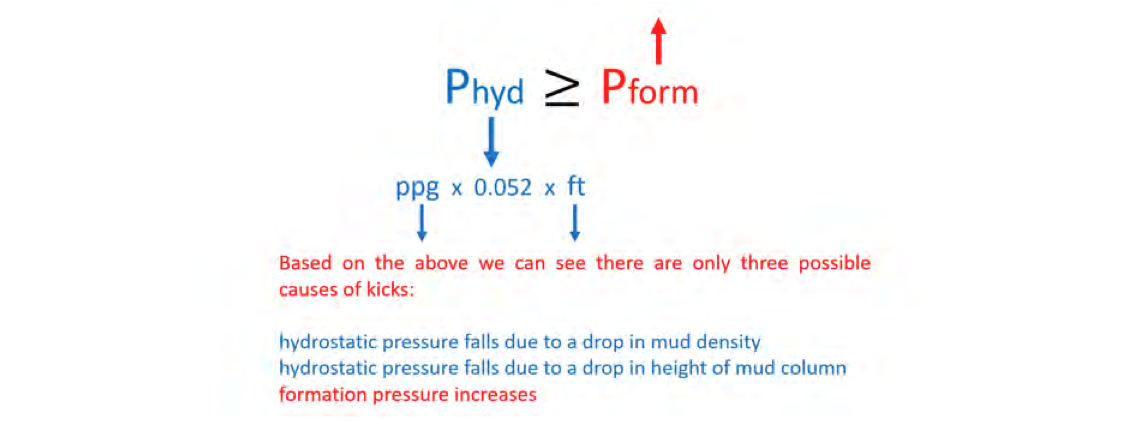

Where Phyd is hydrostatic pressure and Pform is formation pressure. Based on this formula there are only two ways we could lose primary well control when we have it – either hydrostatic pressure drops or formation pressure increases. Using the hydrostatic pressure formula, we know there are only two ways it can go down – either the mud weight goes down or the height of the mud column goes down.

From this we get three possible causes of kicks if we have primary well control:

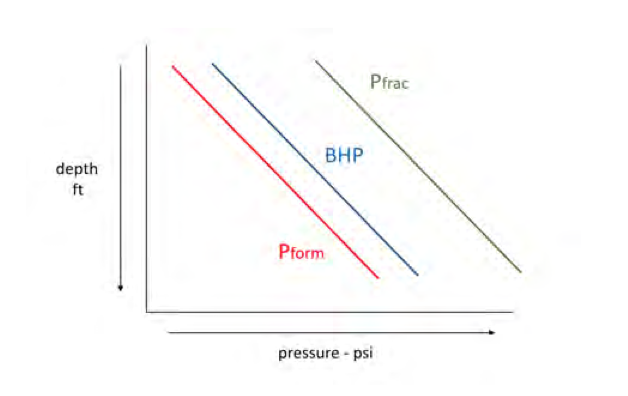

Formation pressure is what formation pressure is so there is not a lot we can do about formation pressure increasing – mother nature has that one. However, we do know that formation pressure is a function of gradient and depth therefore the deeper you drill the higher formation pressure is.

Formation strength (fracture pressure) generally also increases with depth as there is more overburden (not totally applicable in deep water but that’s a different thing right now). The gap between formation pressure and fracture pressure is the window in which we want to maintain our bottom hole pressure. Simplified below as:

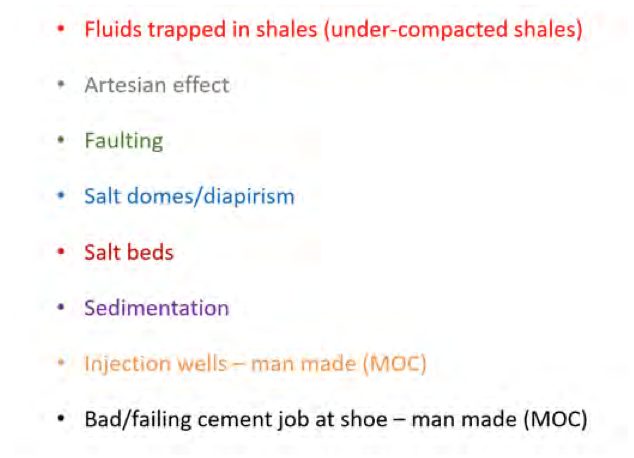

To a certain extent we can predict what formation pressure is and therefore we should be able to maintain our primary barrier in the well. Sometimes we encounter formation pressure that is abnormally pressured, and this can give us problems. Common causes of abnormal formation pressure include:

Fluids can be trapped in shales when there is an impermeable formation, such as a cap rock, that stops fluids escaping over the many thousands of years that formations are laid down. When you drill through a cap rock you can encounter a pressure much higher than expected for the drilled depth.

The artesian effect happens when a formation source is above the rotary table level and most commonly occurs on land drilling operations but sometimes does affect offshore operations.

Gas or water injection is commonly used to increase production in wells but if there is communication between formations can give problems on nearby wells and there are recent case studies where this has happened.

One of the primary purposes of cement is to isolate lower pressure formations further up a well from the higher pressure ones as you drill deeper. If a cement job fails (or was poor in the first place) then this can lead to abnormally pressured formations being encountered.

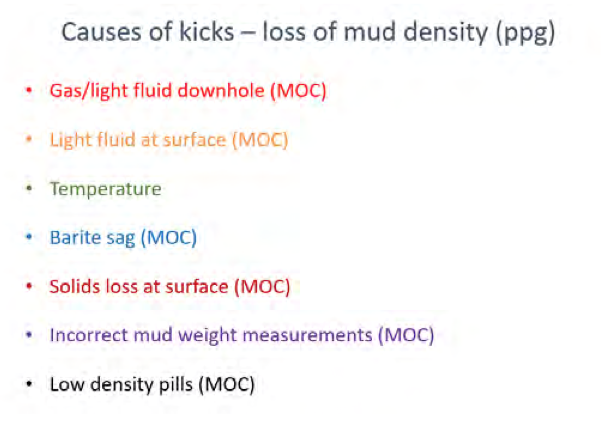

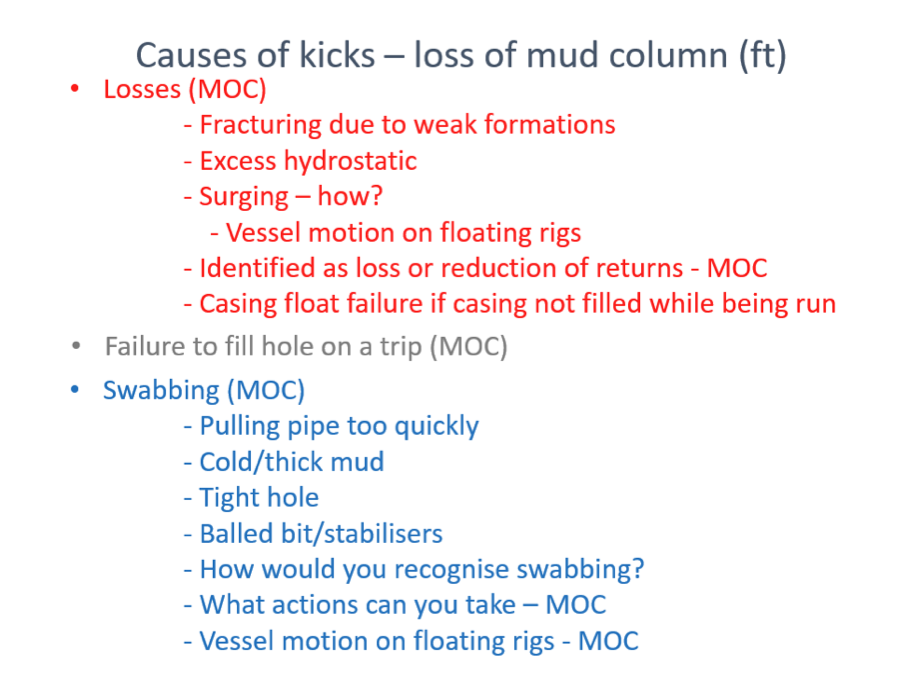

Hydrostatic pressure can reduce if either the mud weight reduces, or the height of the mud column reduces.

Common causes for these are:

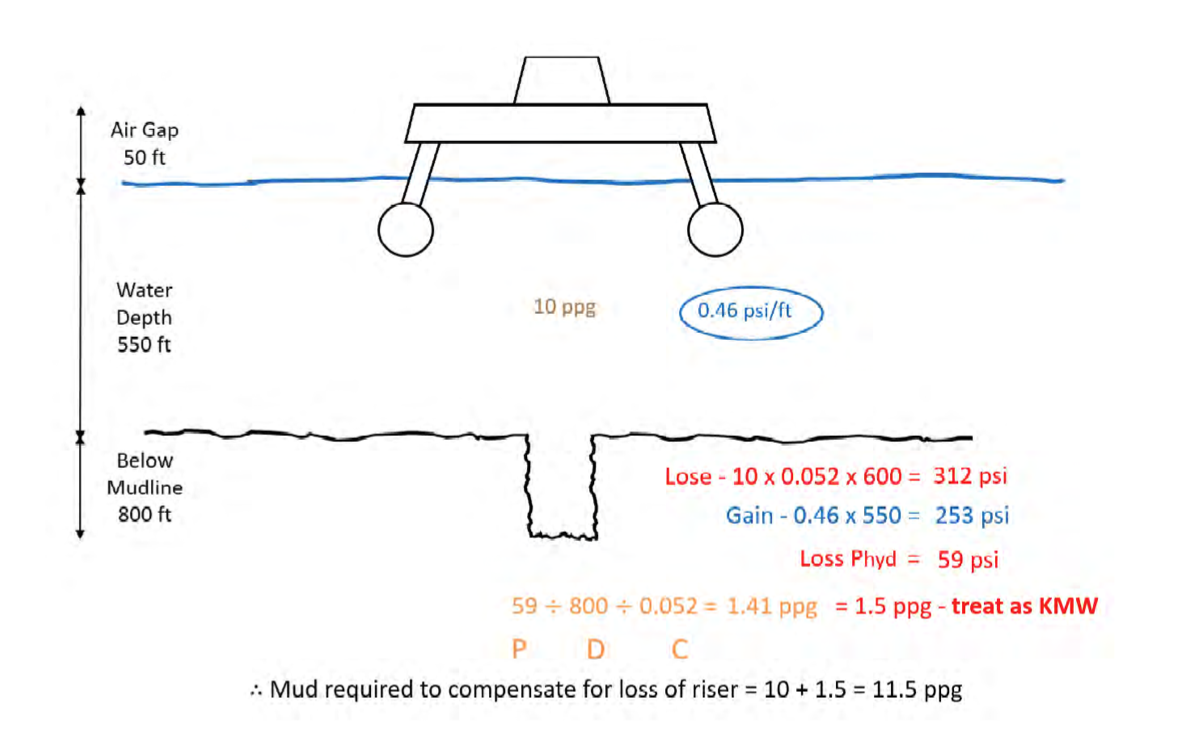

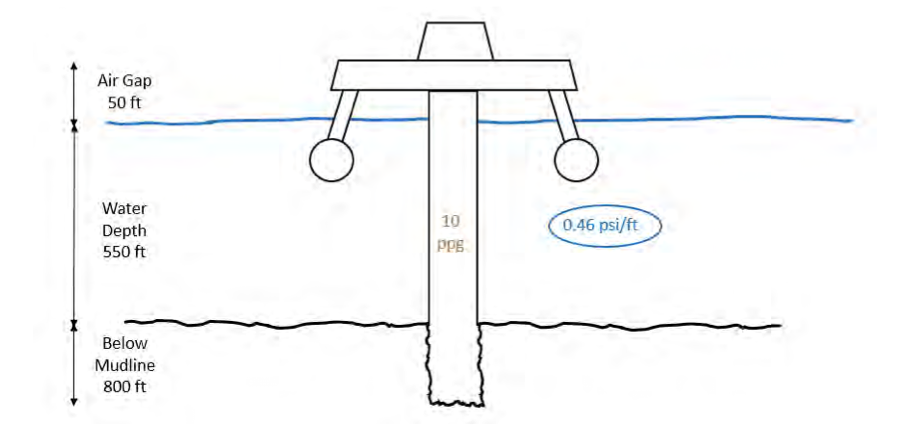

With a subsea BOP stack, it is possible to lose both mud density and height of mud column if the riser was to be accidentally disconnected for any reason. Let’s look at an example.

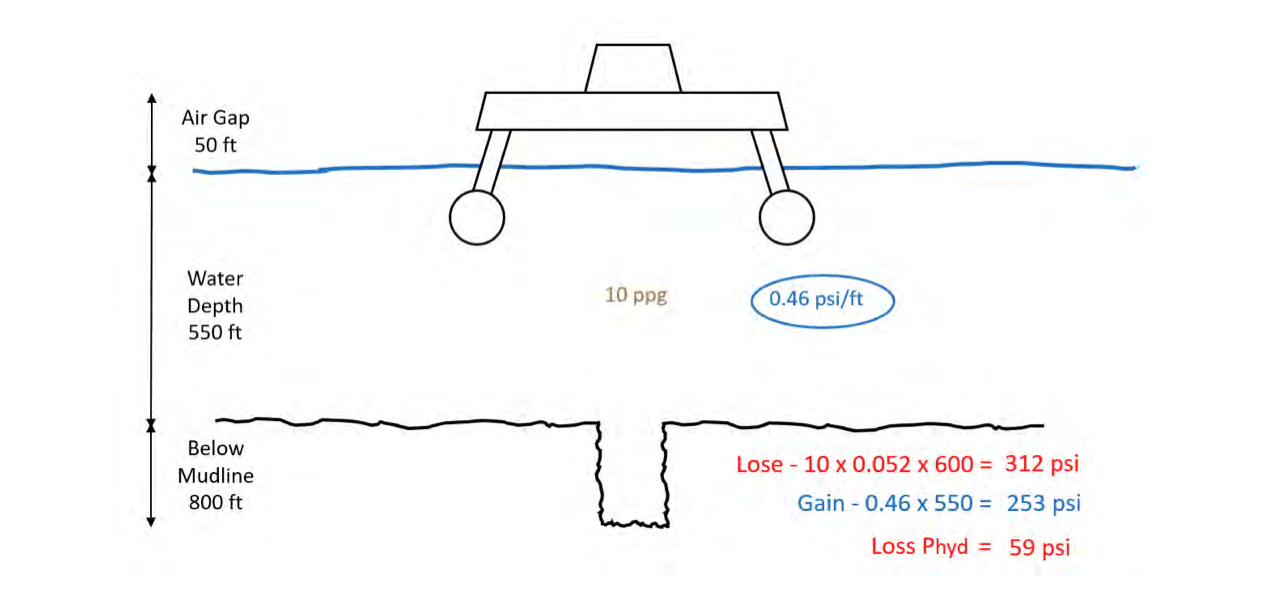

If the riser was disconnected for any reason, then we would lose all the mud in the riser meaning the bottom of the well would lose the hydrostatic head of that mud. The bottom of the hole would however gain the hydrostatic head of the seawater. There would still be a net reduction in hydrostatic pressure acting on the bottom of the hole.

If 10 ppg was a balanced mud weight, then we would go underbalance by 59 psi which would cause the well to kick on us. That 59 psi needs to be recovered as mud weight in the section from the seabed to the bottom of the hole. That mud weight can be simply calculated using PDC and is known as your riser margin mud weight. This increase in mud weight has to be treated as if it was kill mud. For our example we get: